Back in November of 2020, we took a look at the behavioural biases affecting investment decision making. Four years later, post the pandemic aftermath and with a fresh perspective, we review those biases in relation to the pandemic.

Elsevier published an article in 2023 highlighting the impact of the first wave of Covid on investment decision making from the perspective of retail investors. The study found that investors who had first-hand experience with Covid (whether it be their own ill health or that of a loved one) were more likely to increase their investments and savings rate. Investors who experienced the death of a close relative or friend, increased their savings rate by an average of 12%. Investors who experienced trauma in the first wave were more risk averse, while those who did not were more inclined to invest in cryptocurrencies and shares (more risk seeking). These behavioural changes associated with the psychological impact of the virus led to the question of whether or not there have been any long lasting changes to the typical behavioural biases we see within finance.

There are a slew of articles and studies analysing the changes in behavioural finance as a result of the Covid environment. I have chosen to focus on the behavioural biases initially highlighted in our 2020 newsletter, mapping the findings of some of the post-Covid research to them.

Overconfidence

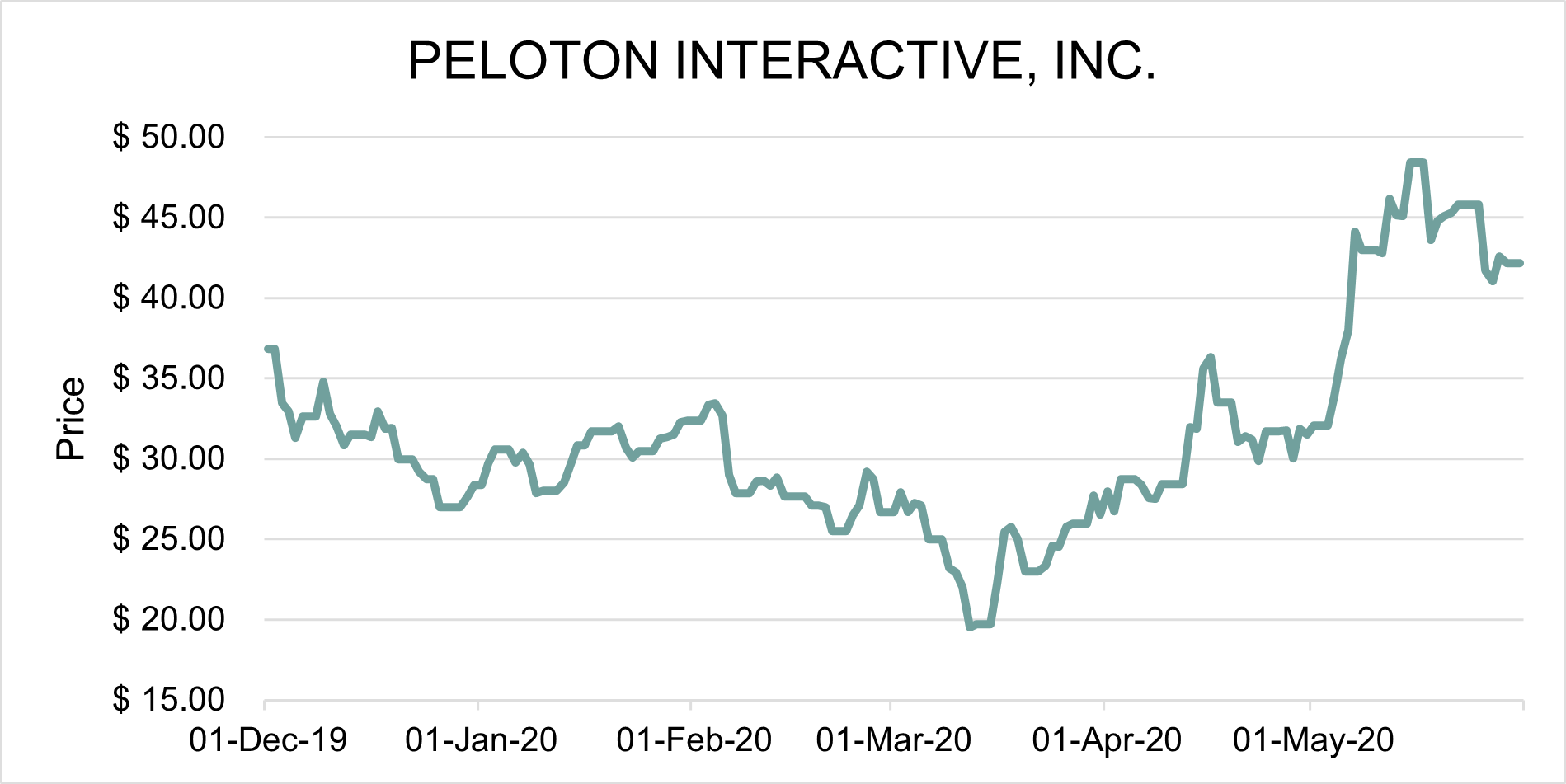

Overconfidence bias is used to describe the perceived accuracy of one’s own decisions, enhanced by the success of those decisions. Abnormal market moves during the pandemic led to many retail investors exhibiting this bias. As the irrationality of retail investors was evident in asset prices, they continued to believe they were successful in asset allocation and investing. For example, inexperienced retail investors made idle stock picks and encouraged others to invest similarly through various social media applications. This spike in demand for traditionally less popular shares, culminated in unwarranted price increases. These price increases were falsely perceived as successful picks. One such example was Peloton.

Peloton gained popularity due to its attractiveness as an alternative way of exercising when gyms and fitness centres shut down during lockdown. As people searched for alternatives, the Peloton stationary exercise bikes were an attractive offering, coming equipped with virtual trainers and exercise plans.

Peloton saw its price rapidly increase over the period March 2020 to January 2021. As more investors piled into the share, the price rose on the back of the increase in demand. Price appreciation was falsely interpreted as an indication of a valuable stock pick, resulting in “credibility” for the pundits. Many investors paid little attention to the company fundamentals and based their decision solely on the popularity of the bikes and the training personalities behind the exercise programs.

Self-attribution Bias

Shanker attributes extraordinary overvaluation of various companies to self-attribution bias, confirmation bias and herding mentality. In terms of self-attribution, investors attributed (unsustainable) large price increases in various share picks to their “investment ability” as opposed to recognising the surplus of free money available and the unwarranted excess flows into these overvalued, often loss making, companies.

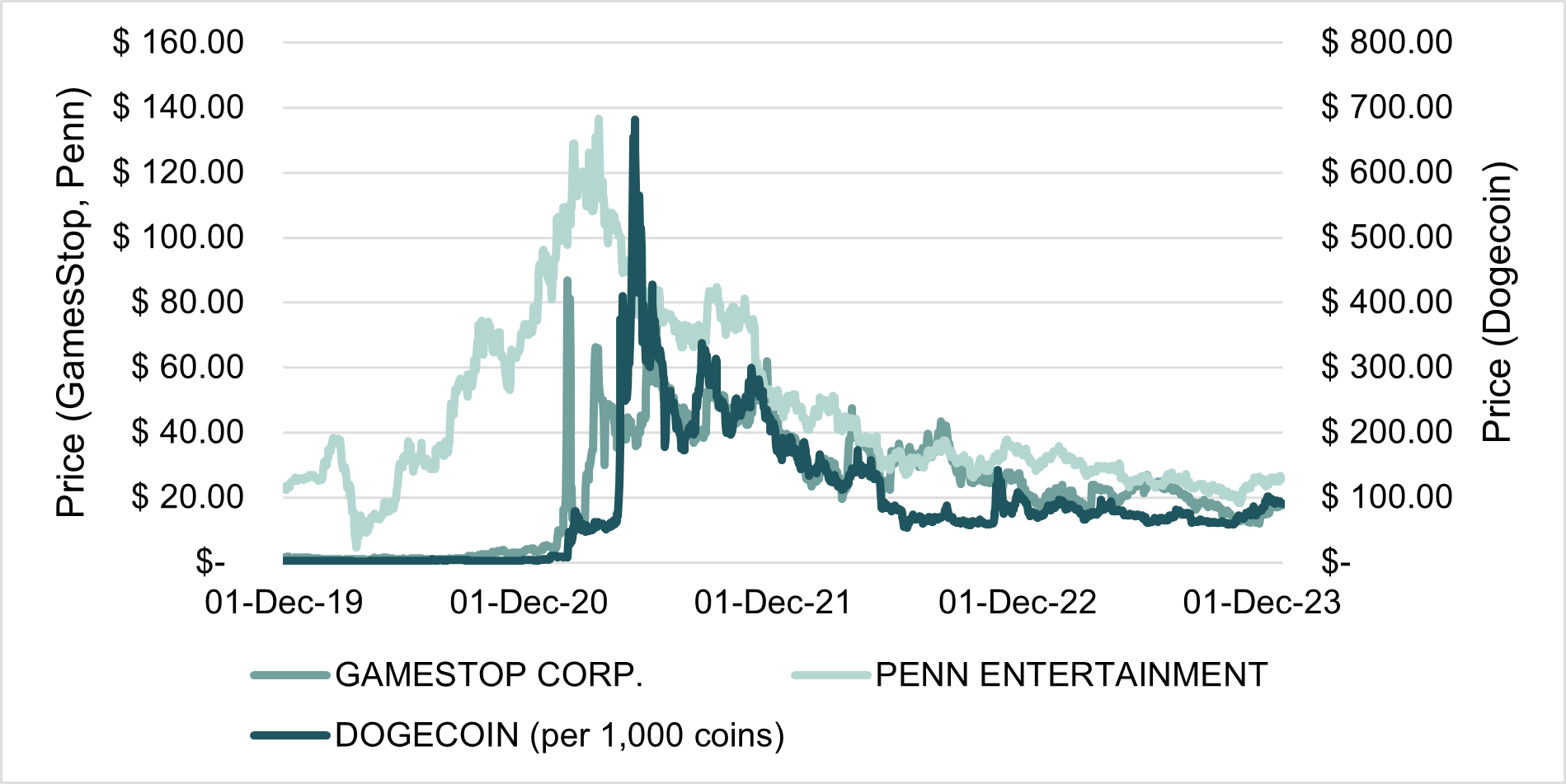

Gamestop, Penn Entertainment, and Dogecoin are all examples of shares which climbed on the back of celebrity posts on social media. Celebrities such as Elon Musk (Tesla CEO), Dave Portnoy (founder of Barstool Sports), Mark Cuban (billionaire entrepreneur and owner of the Dallas Mavericks), and Chamath Palihapitiya (venture capitalist and former Senior Executive at Facebook) were all guilty of manipulating flows to and from the stock market over this period.

As these pundits’ followers invested according to their “advice”, prices climbed. These share price increases were erroneously attributed to superior investment stock picking ability. Without the earnings to back these price increases, shares were trading at unjustifiable valuations.

Market forces eventually prevailed, and all of these meme bets have since fallen back to more realistic valuations.

Hindsight Bias

For the relation to hindsight bias, have we seen the repercussions? Referring back to our article from 2020, many investors believed they were well aware of the risk and likelihood of market turmoil before it happened in 1990 and 2008. Few however made any moves prior to prepare themselves. The pandemic was no different. Investors jumped into shares that were climbing and later (post their re-rating) claimed to have been aware of their inappropriate valuations, despite remaining invested through price declines.

Confirmation Bias

Much of the commentary and opinions during the period of Covid-benefitting share surges focused on the Covid winners and ignored those which were performing poorly. As Shanker highlights, these publications and conversations focus on the positive attributes of these investments and largely ignore the negatives or risks associated with their investment. Positive publications on popular meme stocks provided ‘confirmation’ that they were good investments.

The Narrative Fallacy

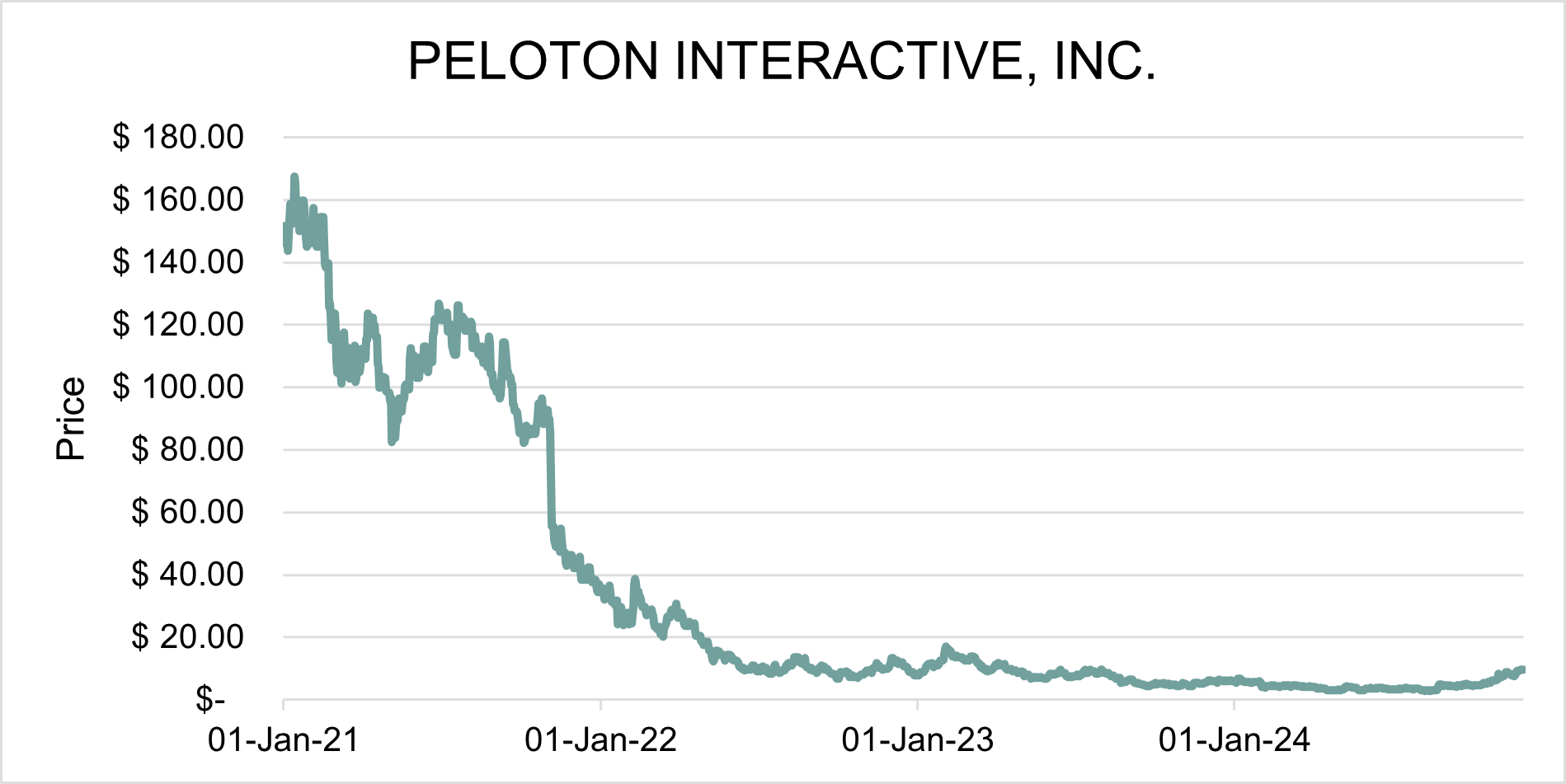

Many Covid stars were evidence of the narrative fallacy. These shares trended up to unrealistic levels on the back of their narrative. Their appreciation wasn’t validated by strong fundamentals, but rather by the perception of their ability to rapidly grow. When the environment started to normalise, these shares quickly came down, bringing investors back down to earth as well.

Peloton’s price appreciation was based on retail investor sentiment and support of the Covid lockdown friendly business model. Retail investors ignored adverse company fundamentals which ultimately led to profits falling and the share price’s collapse from February 2021.

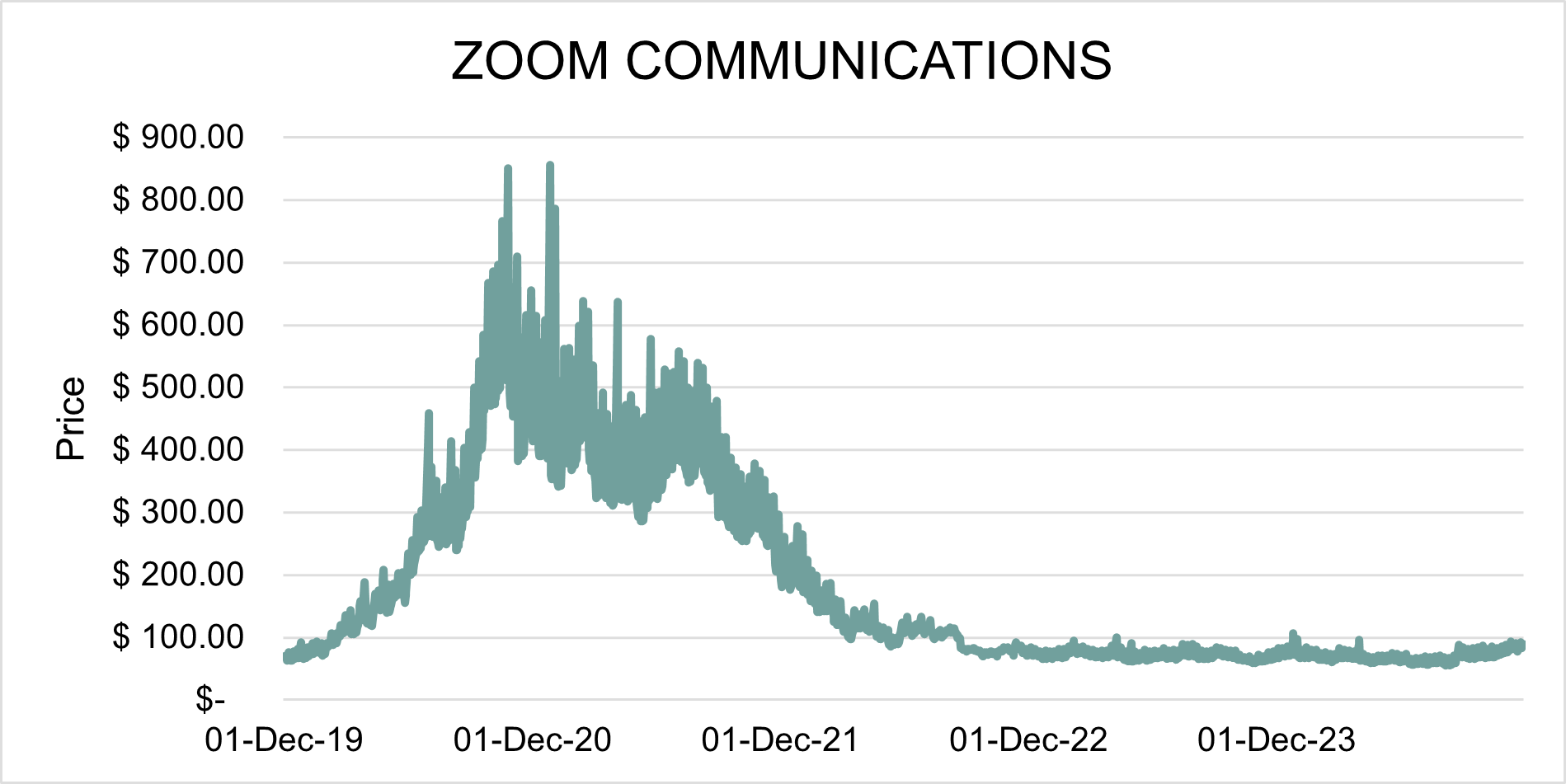

Zoom similarly saw price appreciation based on its narrative. Zoom’s virtual meeting capabilities were overvalued by investors due to its popularity during lockdowns. As the world reopened and people returned to offices, Zoom fell out of favour and the share price corrected.

Representative Bias

Within representative bias, investors place more reliance on the recent past when analysing the current environment. This bias has been recorded as being more apparent in less experienced individuals (by both Alós-Ferrer and Hügelschäfer (2012) and Jha and Singh (2017)), such as those who entered the investment market as a “hobby” during lockdown. Without the experience to refer back to, many of these investors took market behaviours as they experienced them as the norm. Some experienced investors similarly fell prey to this bias, only focusing on the positive performance of popular meme stocks and ignoring historical evidence of bubbles.

Framing Bias

The short squeeze of hedge funds in relation to meme stocks showed an element of framing bias. The hype around “sticking it to the big guy” saw many investors being influenced by the way the trade was framed as opposed to the actual reason for placing the trade. One example of this was GameStop, covered by Bennie in 2021.

Anchoring Bias

As the share prices of meme stocks started to normalise, many investors saw this as a “buy the dip” opportunity. Investors were not concerned that, despite recent falls, shares were still trading at relatively expensive multiples/levels given their historical valuations. Shanker highlights that investors were anchoring their analysis to the most recently traded prices, which were extremely inflated.

Loss Aversion

Shanker identified myopic loss aversion as one of the reasons so many people hesitated to invest at the onset of the pandemic, despite blue-chip, reputable companies trading at all time lows. Investors were so focused on the short-term losses and volatility that they could not see past the over-reaction.

Herding Mentality

The excess of funds flowing into fad shares during the pandemic can largely be attributed to herd behaviour, according to Shanker. As is often the case in a bubble, investors (particularly those with less experience) follow the crowd. Many investors followed popular investment “advice” from various unqualified channels and invested based on the commentary, as opposed to doing their own research and formulating their own opinions. These acts led to overvalued shares travelling further away from their fair values. This mentality was also evident in the actions of investors in relation to Wall Street Bets and Jim Cramer’s commentary on meme stocks.

This herding mentality was evident in GameStop and the resultant short squeeze. Earlier this year, we saw a resurgence of the craze, with GameStop climbing once again off the back of a post on X (previously Twitter).

“You see posts on social media, and it’s like putting big flashing lights out in front of the casino saying, ‘Lots of people are making money — you should come on in. That can be hard to resist.” – Brian Portnoy (financial psychologist)

As prices climb, investors followed the crowd, not wanting to miss out on the opportunity. Those who divested in time made money, but many found themselves worse off as they entered at (unjustified) highs and saw the price fall quicker than they could exit.

The pandemic definitely impacted the way we live and act. The impact on investment behaviours and the resultant market reactions were something asset managers had to adjust to. We have however seen that, over time, market forces prevail and prices correct to more realistic levels. Going forward, it is important to be aware of these biases to ensure one does not fall prey to passing fads which disrupt the market. As long-term investors, we should remain focused on our long-term investment strategies to meet our long term investment goals.

In conclusion, I reiterate Mark Twain’s long standing truism: “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes”.