Conventional wisdom suggests that fixed interest instruments, or bonds (issued by governments and corporations), are low risk investments that offer a known and stable income yield, or coupon, as well as safety of capital. Because of the certainty with regards to income and capital repayment, it is believed that the value of bonds does not fluctuate wildly over the short- to medium-term. Bonds are perceived to be less risky than equities and are oftentimes utilised as a “diversifier” in balanced portfolios.

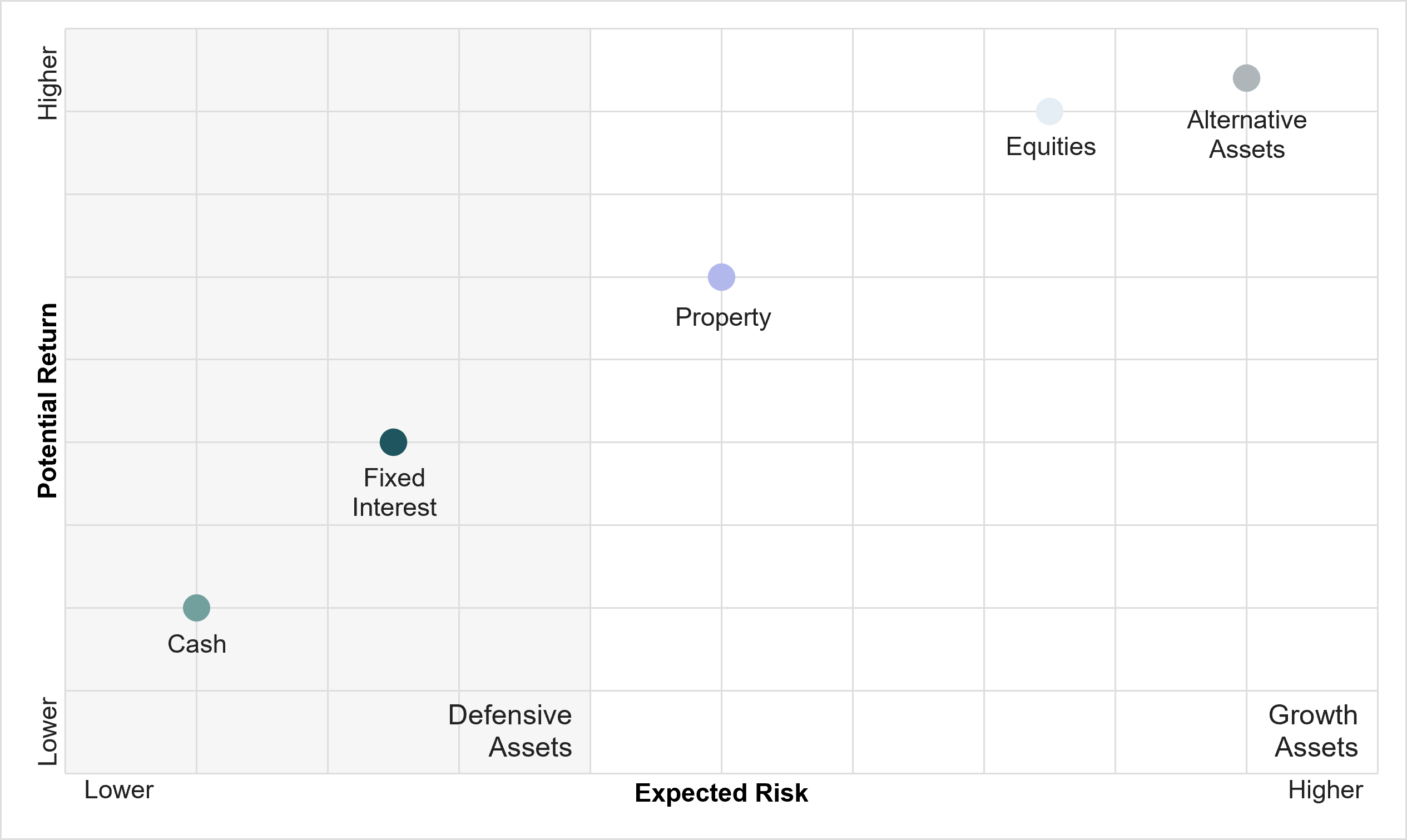

The risk and return characteristics of the various asset classes are depicted in the diagram below. Investment theory states that low returns are associated with low risk and vice versa. On the risk and return continuum, fixed interest instruments are positioned, alongside cash, in the “defensive” assets group, offering low potential return, but also low risk. Shares (or equities), often referred to as “growth” assets, are positioned more towards the upper right hand corner on the risk and return curve, offering higher potential returns, but at higher risk levels.

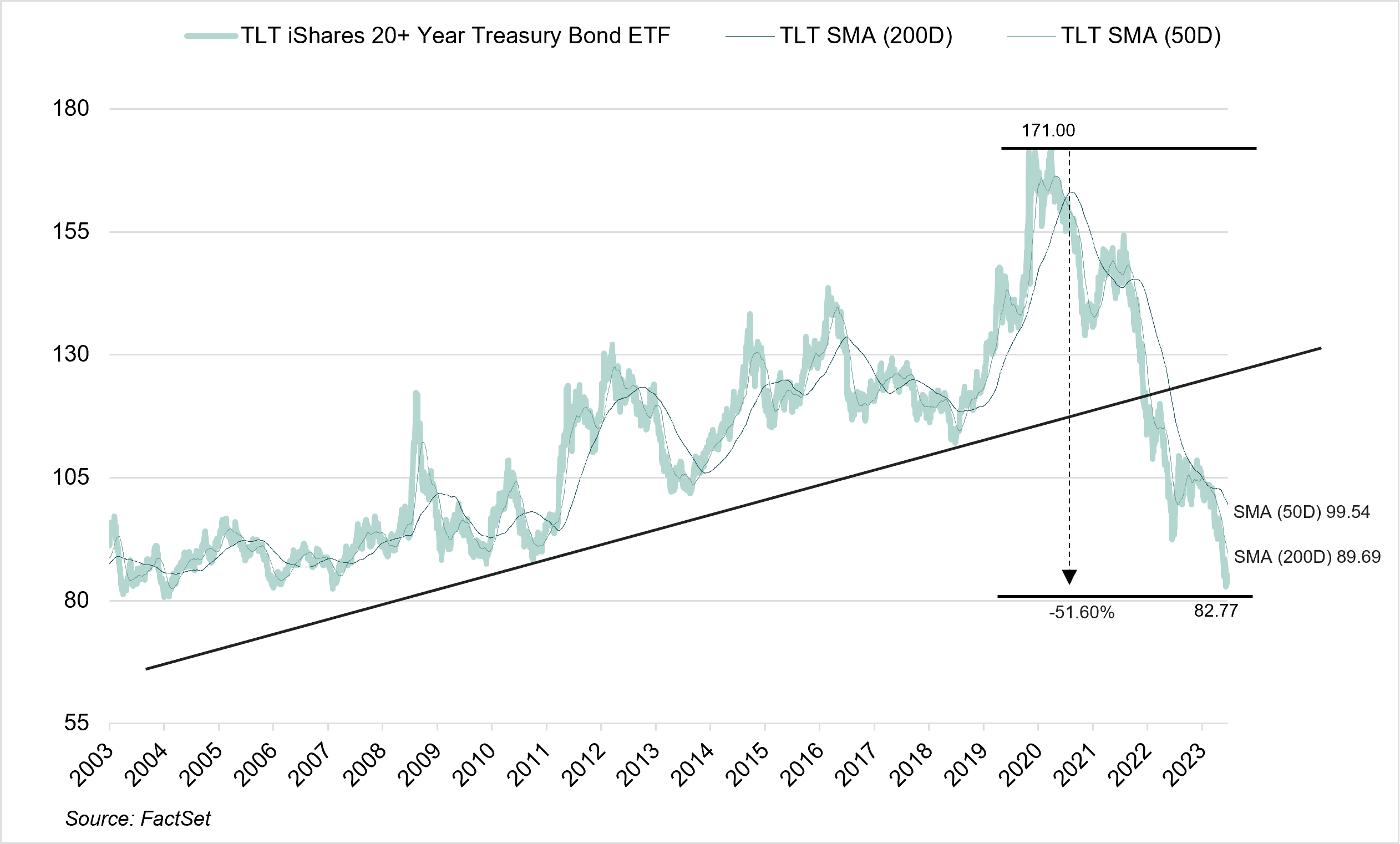

Armed with this knowledge about bonds, one may be forgiven for gasping for breath when evaluating the performance of bonds over the last 2.5 years, especially bonds issued by foreign governments like the US. The chart below shows the performance of the very popular BlackRock iShares ETF (Exchange Traded Fund), which invests in US government bonds with maturities of 20 years and longer. From early March 2020 to date the value of this ETF is down by an eye watering 48%, including interest earned!

Did someone say low risk?

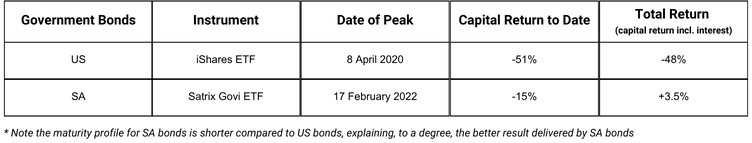

The table below shows the performance of US government bonds and South African Government bonds since their respective recent peaks.

US government bonds lost 51% since 2020 while South African bonds lost 15% since 2022. Adjusting for the interest earned over the respective periods, US bonds delivered a still shocking -48% while SA bonds eeked out a positive return of 3.5%. The interest rate earned on US bonds compared to South African bonds explains the difference between capital – and total returns. While US bonds yielded an interest rate of less than 1% in 2020, SA bonds offered an interest rate of more than 10%, providing a cushion against capital weakness.

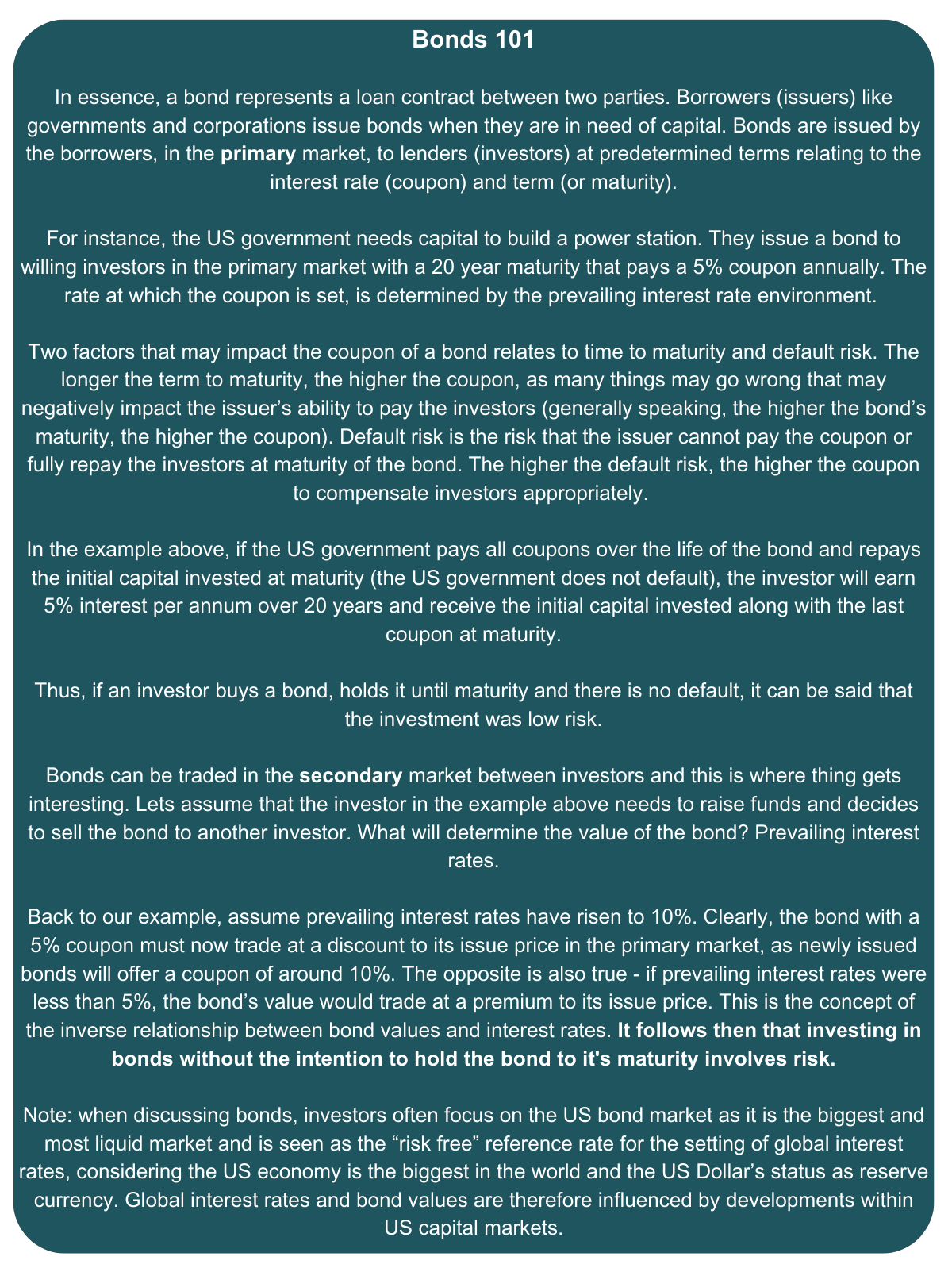

Before we delve into the reasons for the poor performance of US government bonds, a “Bonds Refresher” course may be helpful.

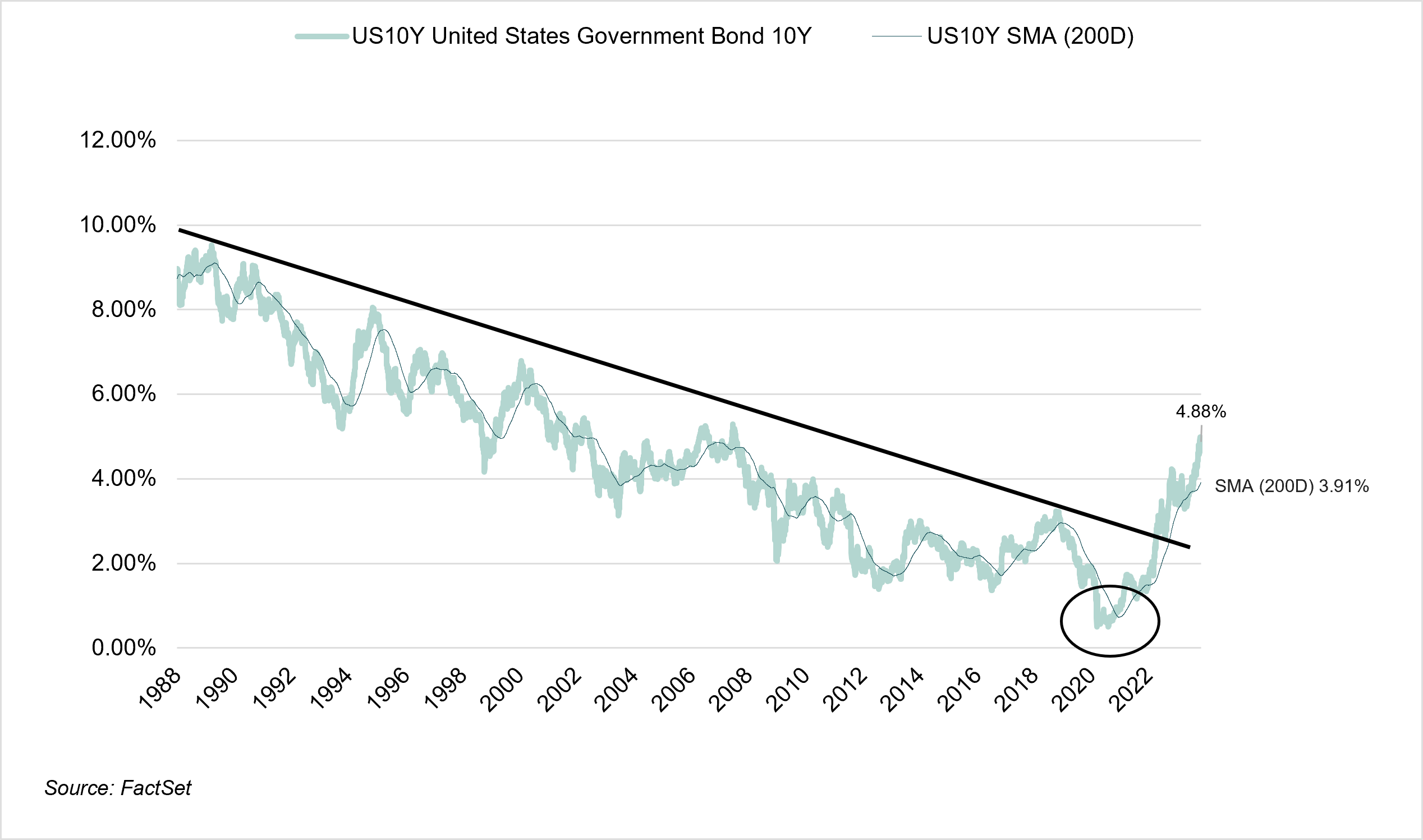

Back to reality. The inverse relationship between bond values and interest rates is what, by enlarge, explains the recent poor performance of bonds. Refer to the charts below of the yield on US government bonds with a maturity of 10 years. After decades of declining interest rates it appears that the trend has changed. As the US Fed started raising the Fed Funds rate (from 0.25% to the current 5.5%) in response to higher inflation (we have written extensively about the risk of structurally higher inflation in late 2020 – The rise of inflation, Part I and Part II), the coupon on newly issued bonds in the primary market has risen and therefore impacted the price of bonds in the secondary market to reflect prevailing interest rate conditions.

Post this significant increase in prevailing interest rates and the subsequent horrific return generated by bonds, the question being asked is whether bonds have corrected sufficiently from being an investment that offers “return-less” risk to one that offers sufficient potential reward for the risk involved?

Like always there are no clear answers but we take guidance from the following factors:

- The benchmark interest rate (the US Fed Funds rate) has risen quickly and significantly from 0.25% to 5.5%, driven by the Fed’s desire to fight rapidly rising inflation. It appears that inflation has become more ingrained into the financial system and that interest rates might be kept higher for longer. We believe, for reasons discussed in our newsletters of 2020 (The rise of inflation, Part I and Part II), that it is likely that inflation will remain high and may increase into the medium term (there will be cycles of easing inflation, but structurally, the pressure is expected to be upwards).

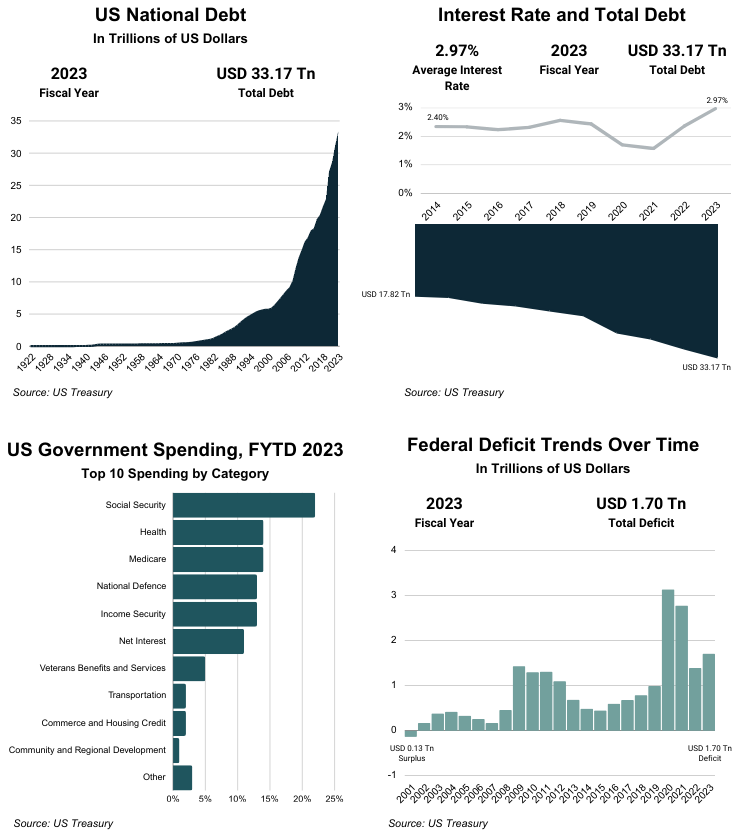

- Increased issuance. The US Federal government is running a sizeable budget deficit, nearly 6% of GDP (USD 1.5 trillion). This is quite a hefty deficit, especially considering that the US National debt pile is sitting at nearly USD 33.5 trillion! Funding the deficit at higher interest rates will place pressure on the US National budget, with interest servicing costs already at almost 15% of US National expenditure.

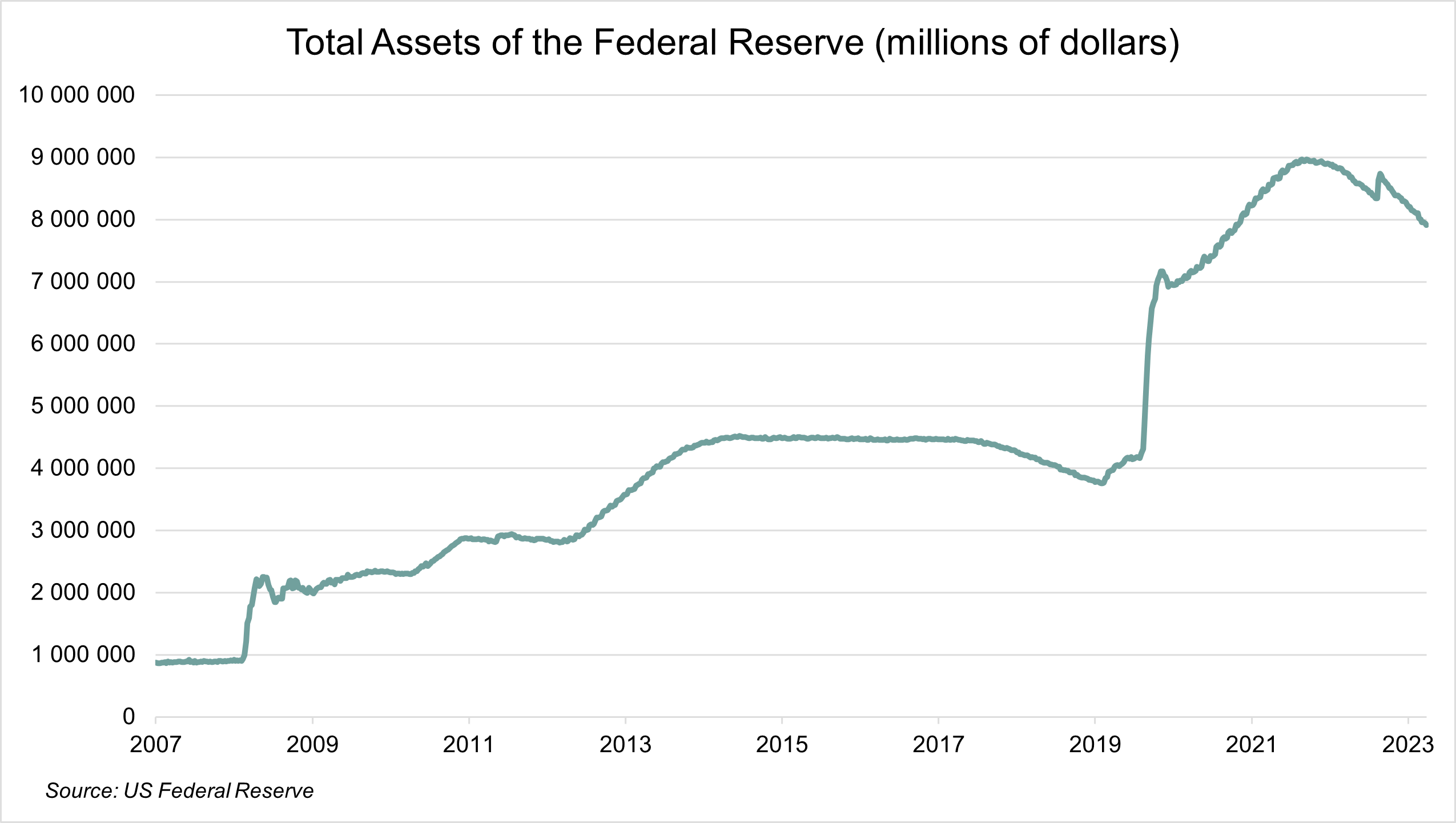

- Quantitative Tightening (QT). Through Quantitative Easing (QE) during the Great Financial Crises of 2007/8 and during the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic, the US Fed accumulated a large Treasury bond portfolio to support capital markets. This is being unwound through QT and the Fed has already cut its holding by approximately USD 1 trillion. This is in effect increasing the supply of bonds during a time when they are under pressure.

- Other central banks reducing holdings. The Chinese have been long-term holders of US Treasury Bonds, but have reduced their bond holdings by USD 200 billion during 2023, additionally increasing supply.

- Recession fears. A recession in the US economy would arguably be a positive for interest rates and bonds. Typically, a recession is accompanied by slowing inflation and weakening labour markets which will give the Fed the ability to cut interest rates into a weakening economy (especially seeing that from a level of 5.5% in the Fed Funds rate, they have room to cut). However, we believe that this respite might be short lived as a weakening economy will put pressure on US tax revenues which will negatively impact the US’ ability to service debt.

All being said, interest rates and bond yields have risen sufficiently to a level where the real yield (i.e. the yield after taking into consideration inflation), is positive, a much healthier situation than 3 years ago when real yields were negative.

Time will tell whether this is sufficient reward as compensation for the risks highlighted. We have not invested in bonds in a meaningful way and have not been impacted by the carnage in bond markets, however, we have recently started to establish exposure in a measured approach and will act fleet-footedly should circumstances change.