The stability of the banking sector is crucial for the overall health of an economy, as they provide various financial services to individuals, businesses, and governments. In effect, banks facilitate capital flows in the economy. Whether it is depositing money, taking out loans, or transferring funds, banks are the backbone of our financial system. In this newsletter, we will explain how a bank works, the risks that banks face, how bank runs happen, and a brief history of the recent bank crises.

How a bank works:

Banks serve as intermediaries between savers and borrowers. They accept deposits from customers and lend those funds to borrowers who need them.

The deposits a bank receives are essentially their liabilities, as they will have to repay them in future. The interest that they pay on funds deposited with them is the cost of having those liabilities. Banks invest the money they receive from deposits into various financial products, such as: loans; shares; bonds; and other securities. These investments represent a bank’s assets. Banks make a profit by charging a higher interest rate on loans (assets) than they pay on deposits (liabilities). This difference is called the “spread,” and it is the primary way banks make money.

The value of a bank’s assets (investments) must exceed its liabilities (deposits) if it is to return deposits to customers.

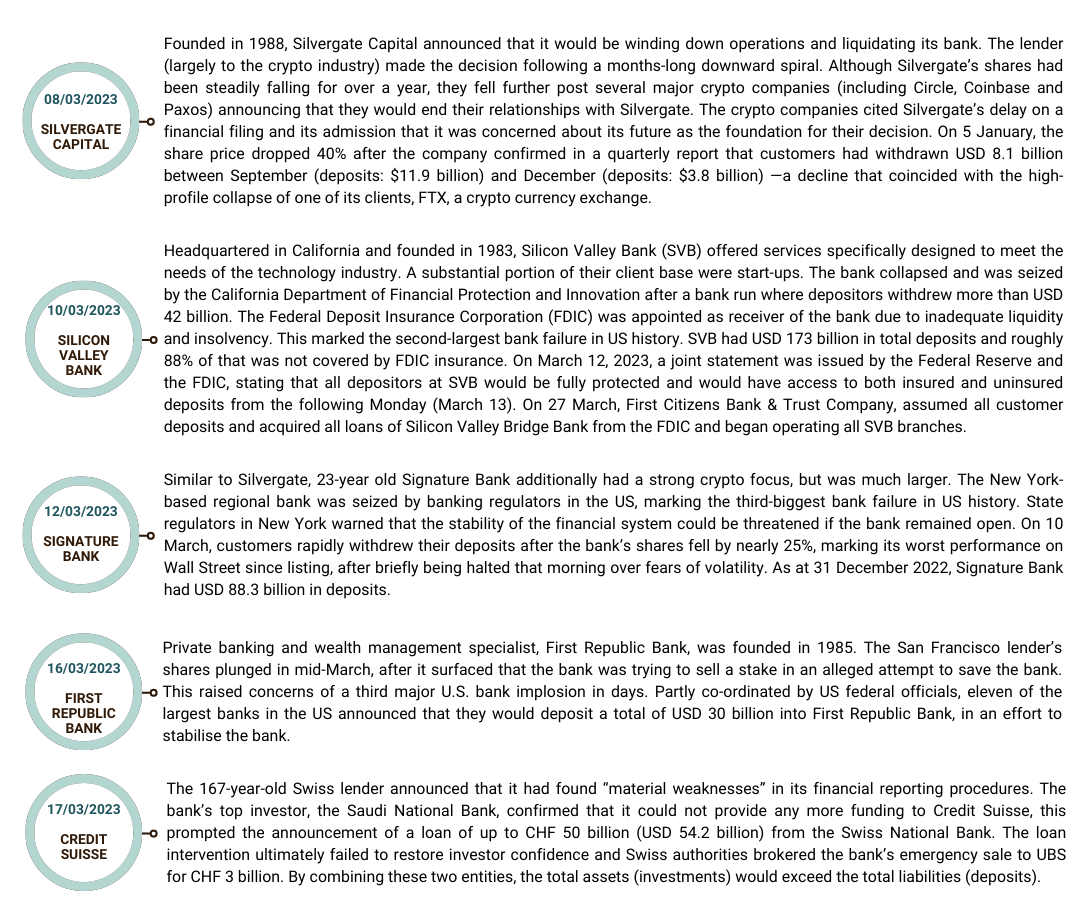

March was a tumultuous period for the global banking industry. Several banks, mainly regional institutional banks in the United States, faced large deposit withdrawals. The chaos was not contained in the US, nor was it solely regional banks making the headlines. Global players similarly came into the spotlight, with the most noteworthy being Credit Suisse. The significantly negative impact on global sentiment surrounding the banking industry which ensued necessitated the intervention of global monetary authorities to restore calm.

Herewith a timeline of how these events unfolded:

Putting deposit size into context

As at the end of September 2022, South Africa had combined deposits, across all banks, for residents and non-residents, of USD 293 billion (CEICdata based on information provided by the South African Reserve Bank). Deposits at SVB and Signature bank totalled approximately USD 261 billion.

Banks face several risks, including: credit; market; liquidity; and operational risk.

Credit risk

Credit risk is the risk that a borrower will fail to repay their loan. This failure to pay is referred to as defaulting. In the event of default, a bank will usually seize the collateral that was provided by the borrower and sell it to recover some of the losses incurred.

Operational risk

Operational risk is the risk of losses due to inadequate or failed internal processes, human error, or external events. It could include, but is not limited to, criminal activity. For example, the risk of being misled into paying customer deposits into an erroneous bank account is an operational risk.

Market risk

Market risk is the risk of losses due to changes in interest rates or other market conditions.

As rising interest rates contributed significantly to the failures mentioned above, the market risk associated with fixed income instruments, such as bonds, is discussed below. For the purposes of this newsletter, the market risk of other instruments is not discussed.

Fixed income as an asset class refers to any instrument which pays a predictable income stream and where there is certainty on the selling price at some future date. Cash and money market investments are considered fixed income in nature. There is certainty that you will receive all of your capital at the end of the term and earn a set interest rate for the duration you keep the funds in the investment. Bonds are similarly fixed income instruments. Bonds are longer-term contracts, based on the same premise. When you purchase a bond today, you have certainty on the interest or coupon that you are going to earn and the capital or nominal value you will receive upon the maturity date.

The value of a bond is inversely related to interest rates. As interest rates increase, the value of a bond will decrease. An important feature of a bond is its “Nominal” or “Face Value”. This is the value that the bond holder will receive when the bond expires. Although the price of a bond may fluctuate during its life, the ending value (at maturity) is contractually fixed.

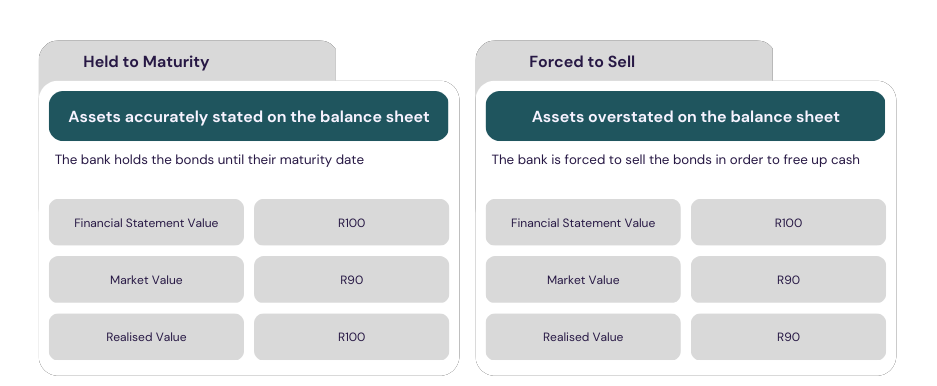

When a bank plans to hold bonds until maturity in order to receive the Face Value, it will classify those bonds as “Held-to-Maturity”. When an instrument is classified as Held-to-Maturity, it is recorded at its “maturity value”, the Face Value in the case of a bond. Banks intending to hold bonds until maturity will record these instruments as assets on their balance sheet at their Face Value.

If the bank actually holds these bonds until maturity, it poses no problem; the bank will receive the Face Value at maturity. If the bank is forced to sell these bonds prior to maturity, in order to raise cash, and the market value is below the Face Value, the bank will only be able to realise the market value of the asset. In this instance, the realised value is lower than the reported value and the assets of the bank are overstated. The table below illustrates this concept.

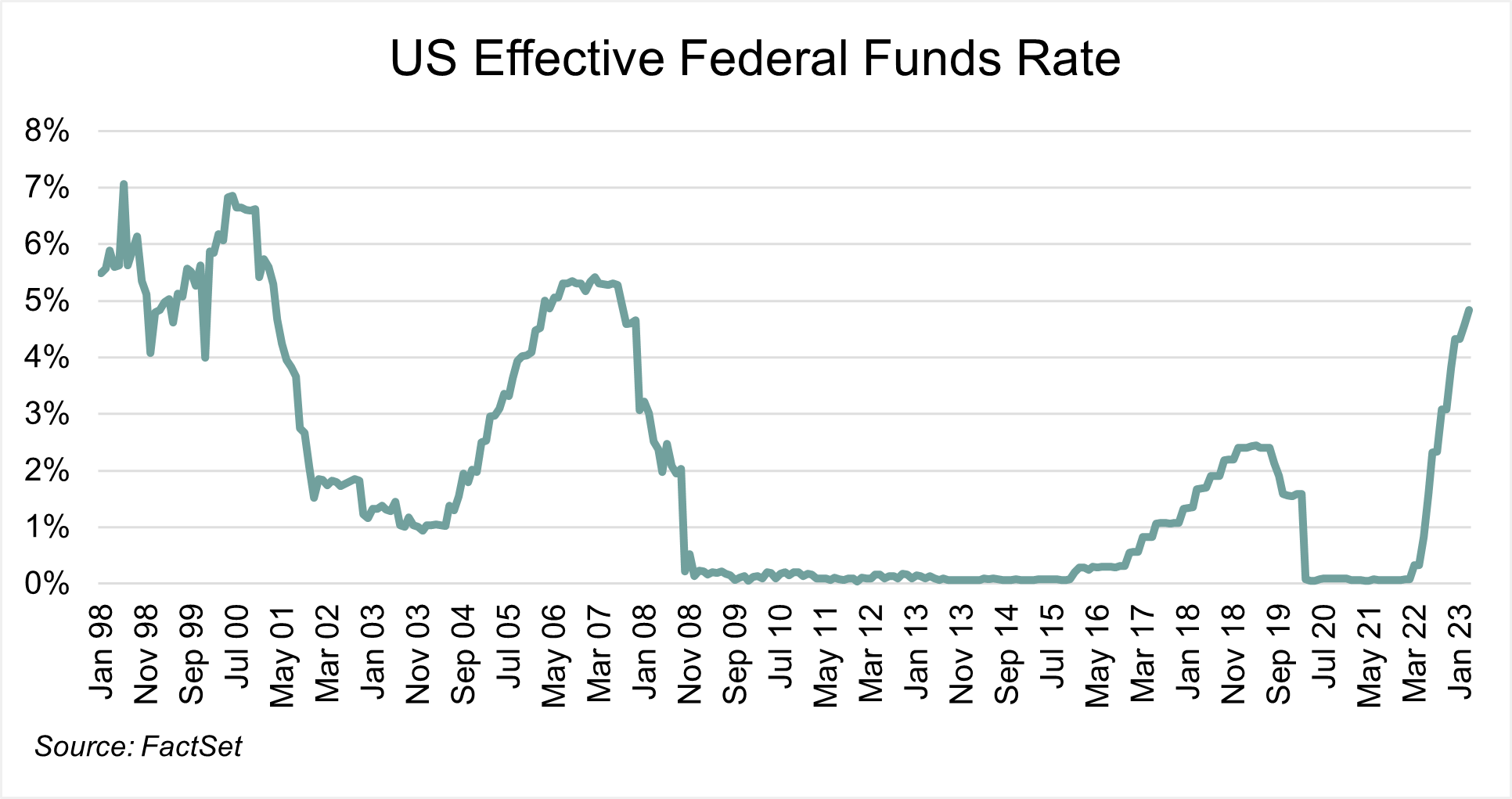

As depicted below, interest rates increased sharply during 2022 and into 2023.

The value of bonds decreased in lockstep.

The decrease in value is not a problem for the bondholder if the bond can be held until maturity as the bondholder will receive the face value. If however the bondholder is forced to sell, the sale will be at current market prices and a loss will be realised.

Liquidity risk

Banks are required to invest a portion of the deposits that they receive into assets that are easy to sell (liquid). This is done so that deposits can be repaid if customers want to withdraw their money. These investments will be classified as “Available for Sale” which mean that these investments will be shown at their current market value in financial statements.

If the value of these “Available for Sale” assets is inadequate to cover the deposit withdrawals, the bank will need to sell some of the “Held to Maturity” assets to make up the shortfall. This could lead to losses as described in the previous section. As these losses accumulate, the value of the assets can fall below the value of the liabilities (deposits), at this point a bank is deemed to have failed.

Liquidity risk is closely related to bank runs.

How bank runs happen

A bank run occurs when many customers withdraw their deposits from a bank in a short period, causing the bank to run out of cash. This does not mean that the bank is insolvent, but that it cannot sell the assets that it purchased quickly enough to repay deposits. Bank runs can be triggered by rumours, news reports, or a loss of confidence in the bank’s ability to repay its depositors. Bank runs can be devastating for a bank should they be unable to repay all of their depositors. The inability to meet withdrawal requirements may ultimately lead to failure. In the past, the sentiment towards a bank that experienced a bank run was negative. These banks struggled to recover and investors became concerned over the overall health of the economy.

As highlighted in the timeline above, the banks that failed serviced niche customer groups. In the case of Silvergate and Signature Bank, it was crypto currency (like Bitcoin) related services and for SVB it was technology startup companies. Due to the customer base being highly concentrated, customers acted in harmony demanding their deposits from these banks. Many were additionally regional banks who do not operate globally.

After running out of cash, these banks were forced to sell the bonds they invested in at substantially lower values than what they had expected to sell them for at maturity (Face Value), resulting in the realisation of these (paper) losses.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) is a US body that insures deposits of US customers at US banks. Not all deposits are insured and normally only the first USD 250 000. In the case of SVB, the FDIC announced that all deposits would be repaid – even those above the threshold, as most of SVBs clients were businesses with very few deposits below the threshold.

The purpose of this insurance is to protect the majority of individuals from bank failures and to minimise the risk of bank runs.

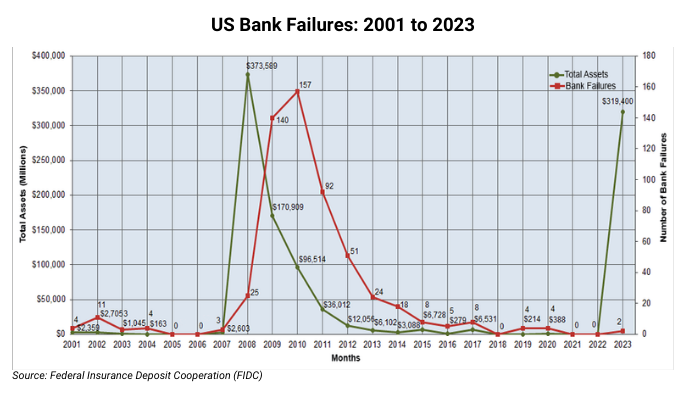

How does 2023 compare to the Great Financial Crisis of 2008

The history of bank failures in the US

As can be seen from the information in the graph, although the number of failures in 2023 was much smaller (only two), the total assets affected were just slightly lower than during the financial crisis of 2007/2008.

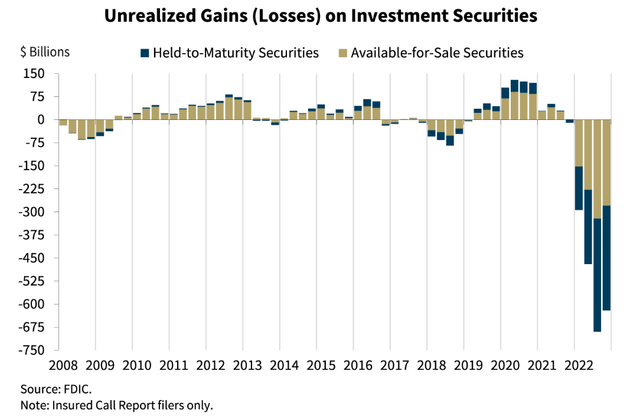

The FDIC monitors deposits insured by them. The next graph shows the cumulative profit/loss across all insured deposits held by US banks. The information is categorised according to its classification, either “Held to Maturity” or “Available for Sale”. This represents the potential losses that banks would need to realise if they were forced to sell these investments to repay deposits if they ran out of cash during a bank run.

It is worth noting that the data in the graph only covers insured US deposits, thus the global situation could well be worse.

Conclusion

Many market commentators have argued that the affected banks did not have a diversified customer base, were regional banks, were mismanaged or had long standing problems (Credit Suisse) and therefore the problem is contained. The market was additionally calmed post other US banks and the Federal Reserve stepping in during the turmoil.

Given the growth in global debt on the back of a prolonged low interest rate environment, moderate increases in the level of interest rates have a large impact on economic participants. The increases to the fed funds rate have been aggressive and we may see further rate hikes. In the fight against inflation, interest rates may also stay higher for longer than the market anticipates. Couple this with human herd behaviour, where panic can spread rapidy (contagion) and there is the possibility of further bank runs. Although measures were taken to stabilise the banking system, we may not be out of the woods yet.

We did not have meaningful exposure to offshore banks (especially regional banks). Volatility creates opportunity and banking shares have come under pressure. We will be watching offshore banks closely to add exposure in portfolios if appropriate and the risk and potential return is favourable.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Henk Myburgh, CFA®- Head of Research

After completing a BCom Econometrics and MSc in Quantitative Risk Management at the North-West University, Henk Myburgh (CFA), started his career in financial risk management at HSBC. He also worked at Sanlam Capital Markets, where his focus was on consolidation of financial risk across the firm and management of risk on a holistic basis. In 2018 he founded AlQuaTra, a quantitative private hedge fund.