We have been writing about inflation since late 2020 and believe it’s safe to say that inflation has become a significant problem facing global financial markets. I am not going to regurgitate the inflation “story” or dwell on all the drivers of inflation, but would like to make a few remarks on the issue:

- we believe global inflation to be structural in nature and, although there may be some cyclicality in inflation in the short- to medium-term, longer term the pressure will remain;

- an important aspect of “sticky” and increasing inflation is the psychological aspect of it – once higher inflation gets embedded in economic participant’s expectations, this impacts forward planning and the expectation for higher prices are passed through the entire value chain, so to speak;

- reporting on financial results during the last quarter, General Motors, Ford and General Electric, amongst others, have confirmed their experience that they have not seen any let up in logistics problems and pricing pressures; and

- the US Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) language with regards to monetary policy has changed significantly. Jerome Powell has recently commented that the FOMC will use every tool at their disposal to bring back inflation to their target range of 2%, even though this may cause some harm to consumers and the economy. How much further can interest rates rise in the US? For context, the long-term average, real (after inflation) 10 year bond yield is approximately +2%. The current real yield is -4,5%…

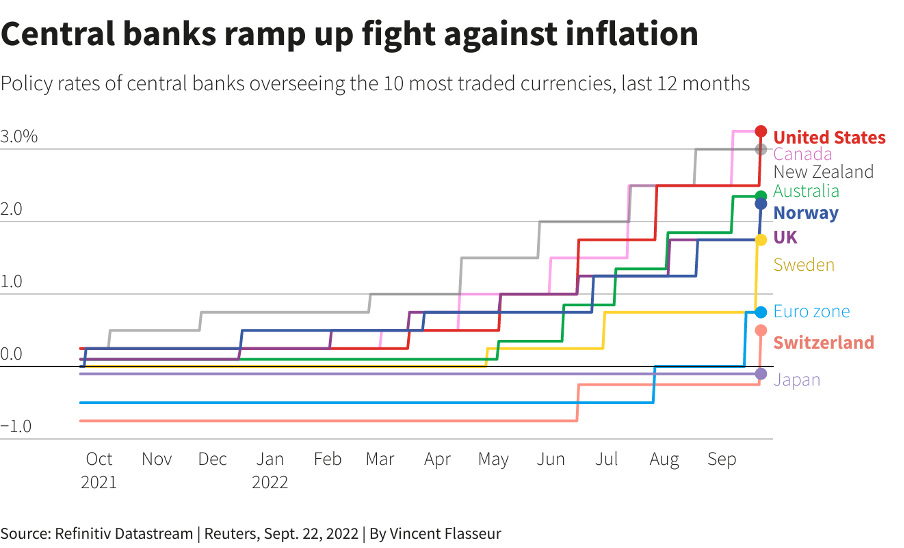

While inflation is still very much making daily headlines in the financial press globally, the focus is shifting increasingly to the impact on monetary policy, economic activity and financial markets. Since the start of the current rate hiking cycle, the central banks of the ten developed economies with the most traded currencies, have raised rates by a combined 19,65%. In fact, most central banks globally are currently raising interest rates in their fight against inflation.

Needless to say, increasing interest rates tend to act as a “brake” on economic activity and market analysts are debating whether the global economy will enter a recession as a result. MIT economist Rudi Dornbusch once said that “none of the post-war expansions died of natural causes, they were all murdered by the Fed.” According to the highly regarded Robert D Arnott, “the motive for this murder is usually to save the economy from incipient inflation by killing the economy”.

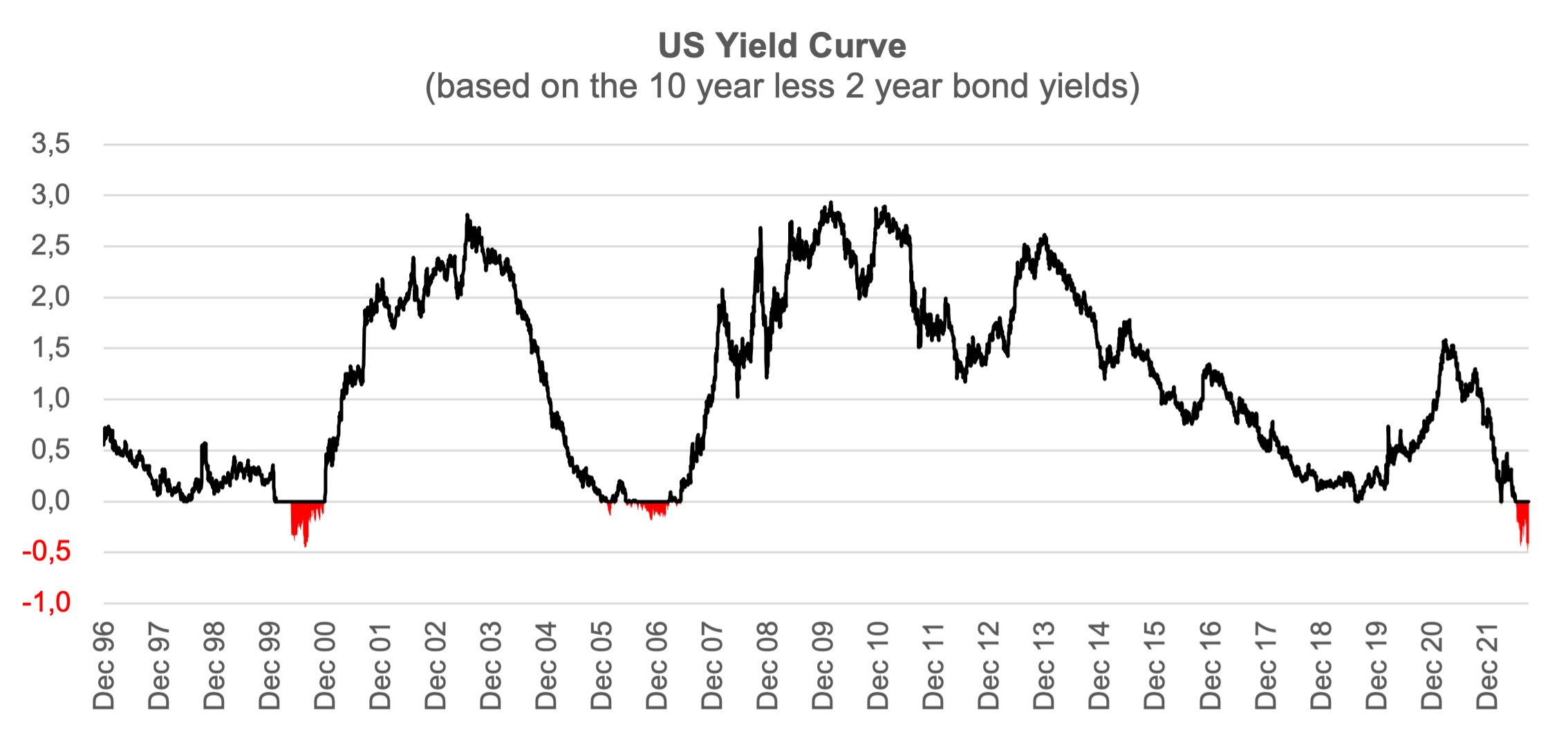

One way to gauge whether an economy may enter recession is to observe the yield curve. In essence, the yield curve is the difference between short-term and long-term interest rates (for instance the 2 year bond yield versus the 10 year bond yield). If short-term interest rates are higher than long-term interest rates, the yield curve is said to be “inverted”. As at 30 September 2022, the yield curve in the United States is inverted with the 2 year bond yield at 4,17% versus the 10 year bond yield of 3,75%. The chart below shows the yield curve over the last 25 years. The areas highlighted in red depict an inverted yield curve.

Research Affiliates Campbell Harvey and Robert Arnott have done extensive research on the relationship between yield curves and recessions. In his 1986 PhD dissertation, Harvey showed that a yield curve inversion has a perfect success ratio in forecasting recessions since 1968. Arnott has suggested that a yield curve inversion doesn’t predict recessions, it causes recessions. The long-term bond yield is mainly a market rate set by the market’s perception of the fair cost of long-term capital, while the short-term bond yield is largely managed by the central bank. If the central bank raises the short-term cost of risk-free capital above the long-term end, it is choosing a rate the market tells us is too high. This isn’t necessarily the case in an economy (Europe or Japan) where the central bank also controls the long end of the yield curve (in policy circles, this is called yield-curve control).

This brings us to capital markets, which are “discounting” mechanisms in that they tend to anticipate what may occur in the future. Therefore, stock and bond markets may “react” to increasing inflation, rising interest rates, inverting yield curves and resulting recessions by adjusting lower (as higher interest rates may negatively impact company profits and affect bond prices which move in the opposite direction to interest rates).

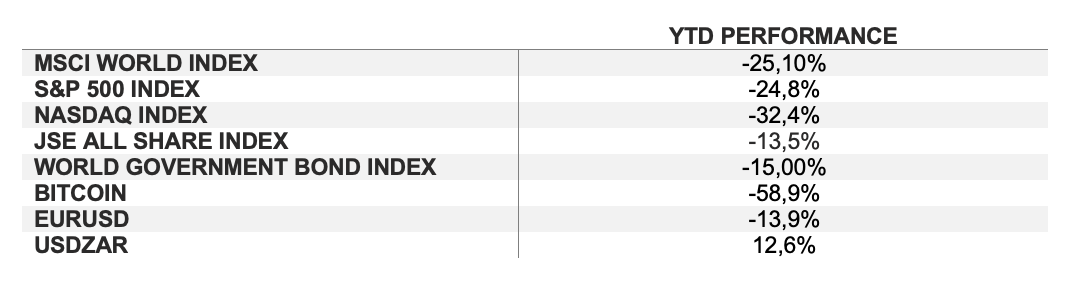

As per the table above, year to date, it appears as though capital markets have indeed adjusted significantly to the downside, as the impact of higher interest rates may have been discounted. A number of other issues have also been plaguing markets, inter alia:

- Geopolitical events in Eastern Europe and Asia

- Quantitative Tapering (the opposite of Quantitative Easing or the so called “printing” of money)

- Economic trouble in the UK

- Strong US Dollar

However, according to Warren Buffett, “It’s only when the tide goes out that you know who’s been swimming naked.” In essence, Warren is saying that higher interest rates, an economic downturn and falling capital markets exposes those who had been taking on excessive risk (debt) when times were good (interest rates were low).

It is conceivable that there may be area’s of higher than usual credit risk which may be exposed by higher interest rates, resulting in further volatility from here. Possible candidates include: European Banks; certain Emerging Markets (those with low foreign currency reserves and budget deficits); complicated financial structures linked to new age instruments like Crypto; or even the Chinese property market.

As always, and in light of the uncertain environment we find ourselves in, we advocate for the following in an investment strategy: diversification, a global vision, focus on quality investments and income, and continued focus on long-term objectives.