The investor’s chief problem—and even his worst enemy—is likely to be himself.

-Benjamin Graham

Often studied in psychology and behavioural economics, are the systemic patterns of deviation from the norm or rationality in judgement, called behavioural bias. In simpler terms, behavioural finance is the study of the influence of psychology on the behaviour of investors or financial analysts, which subsequently have effects on markets.

We all have biases that may cloud our judgement when making day-to-day decisions, and our finances are not exempt from these biases. We often depend on our intuition, but sometimes we are unaware of how our gut feeling may be faulty. These biases then affect how we think, act and make investment choices. In their simplest form biases can be cognitive or emotional. Cognitive biases are illustrated by a tendency to think and act in a certain way or follow a rule of thumb. Emotional biases refer to taking action based on feeling rather than fact.

The emergence of Behavioural Finance

The principal objective of an investment is to make money. In the early years, investing was based on performance, forecasting and market timing, among other things. These factors alone produced very ordinary results. There was also a sizable gap between available returns and received returns which forced us to search for the reasons why this was happening. Researchers later identified that the result was caused by fundamental mistakes in the decision-making process. In other words, investors would make irrational investment decisions. In recognising these mistakes and means to avoid them, and to transform the quality of investment decisions and results, the impact of psychology in investment decisions became evident.

Several years ago, researchers began to study the field of Behavioural Finance to understand the psychological processes driving these mistakes. Thus, Behavioural Finance is not a new subject in the field of finance and is taken into account in popular stock markets across the world when it comes to investment decisions. Many investors have long considered that psychology plays a very important role in determining the behaviour of markets. However, it is only in recent times that a series of concerted formal studies have been done in this area. The results of these studies were at variance with the rational, self-interested decision-maker posited by traditional finance and economics theory.

Understanding the concept of behavioural finance will help investors to select better investment instruments and avoid repeating expensive errors in future.

Traditional Finance Theory vs Behavioural Finance Theory

In order to better understand behavioural finance, we need to take a look at traditional financial theory. Traditional finance theory is based on the following assumptions:

- Both the market and investors are perfectly rational

- Investors truly care about utilitarian characteristics

- Investors have perfect self-control

- Investors are not confused by cognitive errors or information processing errors

Behavioural Finance Theory differs from Traditional Finance theory in that Behavioural Finance Theory’s premise is:

- Investors are treated as “normal”, but not “rational”

- Investors actually have limits to their self-control

- Investors are influenced by their own biases

- Investors can make cognitive errors that lead to wrong decisions

Decision-making errors and biases

Decision-making is a complex activity. Decisions cannot be made in a vacuum by relying on personal resources and complex models, which do not take into consideration the situation.

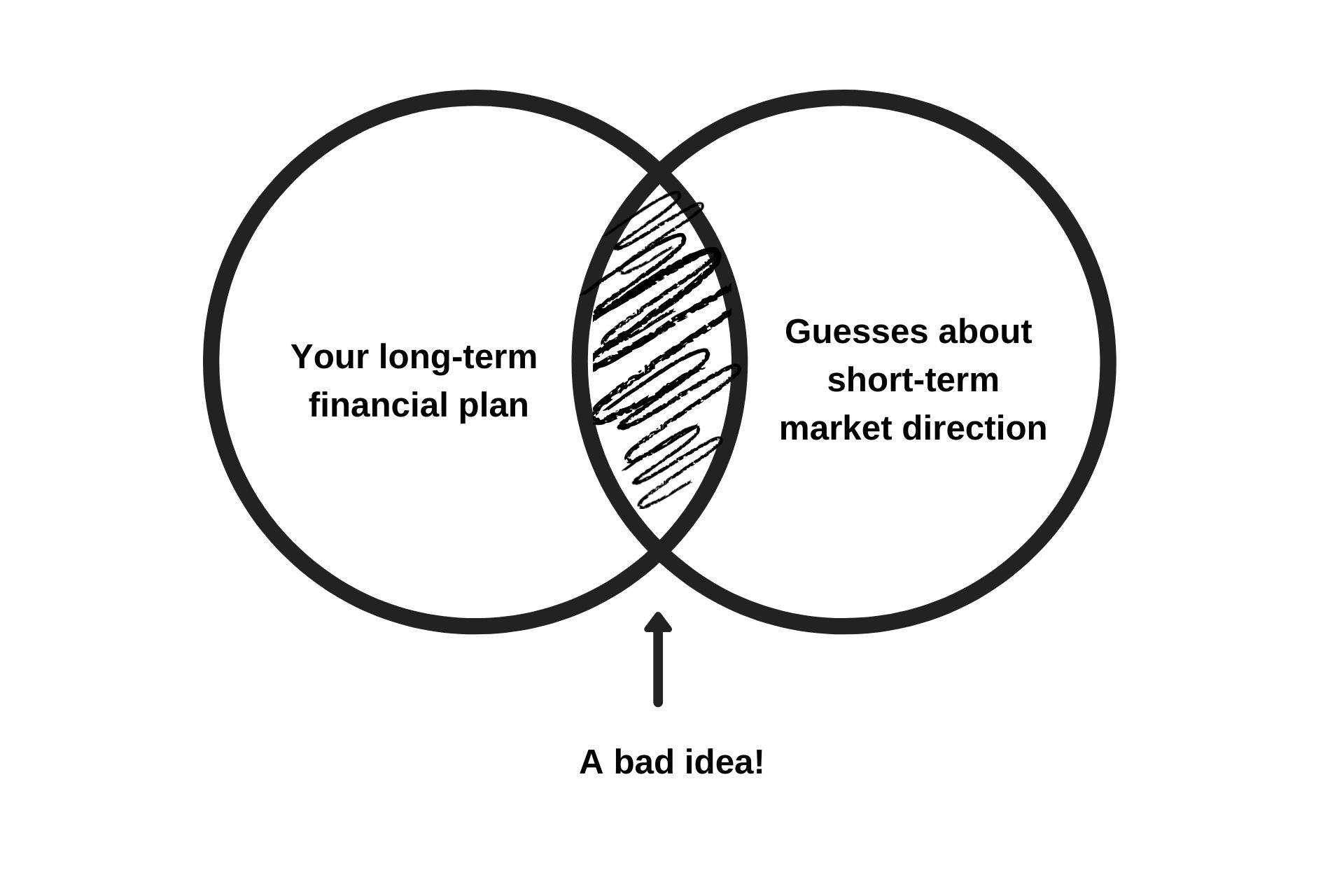

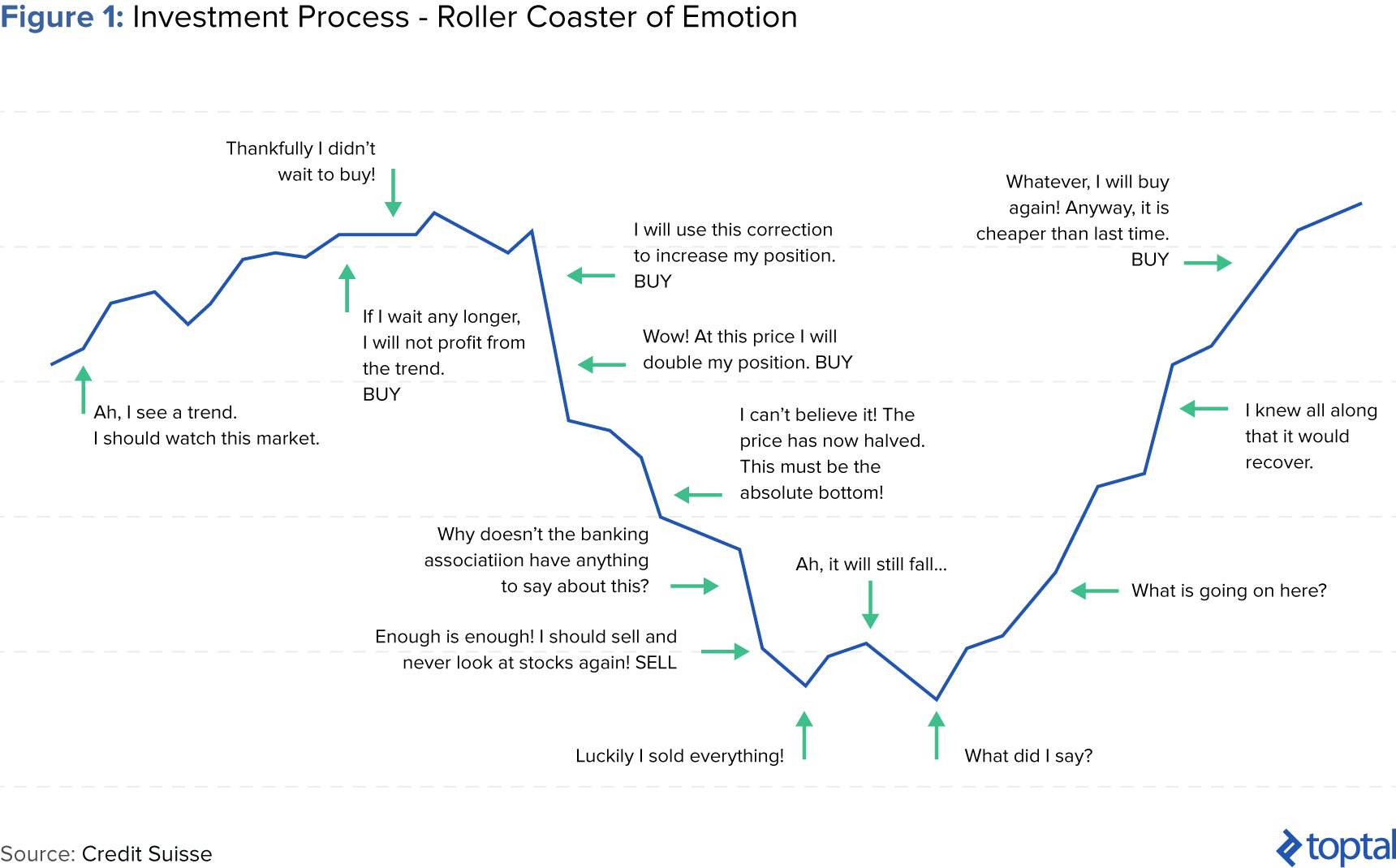

In the investment process, investors often experience the ‘roller coaster of emotions’ illustrated below:

Behavioural finance is becoming an integral part of the decision-making process because it heavily influences investors’ performance. Investors can improve their performance by recognising the biases and errors of judgement to which all of us are prone. Understanding the concept of behavioural finance will help investors to select better investment instruments and avoid repeating expensive future errors.

The most common behavioural biases related to finance include:

1. Overconfidence

Overconfidence bias is a tendency to hold a false and misleading assessment of our skills, intellect, or talent. In short, it’s an egotistical belief that we’re better than we actually are and can cause major problems because it typically leads to taking on too much risk.

- Illusion of control: People, on average, also believe that they have more control than they really do, and this leads them to think situations are in fact less risky than they actually are. Failure to accurately assess risk leads to failure to adequately manage risk.

- Timing optimism: An example of timing optimism is when people overestimate or underestimate the time it takes to do certain things. Investors frequently underestimate how long it may take for an investment to pay off.

- Desirability effect: People overestimate the chance of something happening simply because the outcome is desirable. This is sometimes referred to as ‘wishful thinking’. We make the mistake of believing that an outcome is more probable just because it is linked to the outcome we want.

2. Self-attribution bias

Self-attribution bias, or a self-serving bias is a tendency to attribute favourable outcomes to our skill and bad outcomes to luck. We tend to choose how to attribute the cause of an outcome based on what makes us look best.

3. Hindsight bias

Hindsight bias is the misconception, after the fact, that one “always knew” that they were right. Someone may also mistakenly assume that they possessed special insight or talent in predicting an outcome.

Consider the 2008 financial crisis or the dotcom bubble of the late 1990’s. If your talk to many people now, they may state that all the signs were there, and everyone knew it was coming. However, if you examine the history, you learn that analysts or investment professionals who were screaming that there was a problem at the time weren’t listened to; in fact, they were laughed at and investors largely ignored their warnings.

4. Confirmation bias

Confirmation bias is the tendency of people to pay close attention to information that confirms their beliefs and ignoring information that contradicts it.

Most of us have a really bad habit of only paying attention to information that agrees with our existing beliefs. We also tend to form our views first, and then spend the rest of the day looking for information that supports our views. Our natural tendency is to listen to people and information that agrees with us.

5. The narrative fallacy

One of the limits to our ability to evaluate information objectively is what is called the narrative fallacy. We love stories so much that we let our preference for a good story cloud the facts and our ability to make rational decisions. This means that we may be drawn towards a less desirable outcome simply because it has a better story. Stockbrokers have taken advantage of this fallacy for years, convincing clients to invest in a stock by telling them a great story about the company.

6. Representative bias

Representative bias occurs when the similarity of objects or events confuse people’s thinking regarding the probability of an outcome, and that two similar events or things are more closely correlated than they actually are.

In financial markets, one example of this representative bias is when analysts forecast future results based on historical performance. Just because a company has seen high growth for the past five years doesn’t automatically mean that a specific trend will continue into the future.

7. Framing bias

Framing bias occurs when people make a decision based on the manner the information is presented, as opposed to evaluating the facts. The same facts presented in two different ways can lead to people making different judgements or decisions, and investors may react differently to a particular opportunity depending on the manner in which it was presented to them.

Below are some example of framing in finance:

OPTION 1: In Q3, our Earnings Per Share (EPS) were $1.25 compared to expectations of $1.27

Vs.

OPTION 2: In Q3, our Earnings per Share (EPS) were $1,25, compared to Q2, where they were $1.21

Option 2 frames the earnings report in a more positive light.

8. Anchoring bias

This occurs when people rely too much on pre-existing information or the first information they find when making decisions. For example, if someone was to ask you where you think Amazon’s share price will be in a few months, many people would base their assumption on where the share price is today. We’re starting with a price today, and we’re building our sense of value based on that anchor.

Anchoring bias is dangerous yet prolific in the markets. Anchoring, or rather the degree of anchoring, is going to be heavily determined by how salient the anchor is. The more relevant the anchor seems; the more people tend to cling to it. Also, the more difficult it is to value something, the more we tend to rely on anchors.

When we think about currency values, which are intrinsically hard to value, anchors get involved. The problem with anchors is that they don’t necessarily reflect intrinsic value, and we develop the tendency to focus on the anchor rather than the intrinsic value.

9. Loss aversion

Loss aversion refers to when investors are so fearful of losses that they focus on trying to avoid a loss more than they are focused on making gains. This usually results in people selling their winners while holding their losses. Research in loss aversion shows that investors feel the pain of a loss more than twice as strongly as they feel the enjoyment of making a profit.

Many investors don’t acknowledge a loss as being such until it is realised. Therefore, to avoid experiencing the pain of a “real” loss, they will continue to hold onto an investment even as their losses from it increases, thinking that the loss doesn’t count until the investment is closed. This results in investors holding onto losing investments for much longer than they should have, and most often than not, suffer much bigger losses than necessary.

10. Herding mentality

The herd mentality bias refers to an investor’s tendency to follow and copy what other investors are doing. This is largely influenced by emotion and instinct, rather than by their own independent analysis.

We are hard-wired to herd, therefore, one of the things to be very cautious of is that we find it psychologically painful to go against the crowd. Non-conformity typically triggers fear in people immediately, for fear of being wrong or looking foolish when they go against the crowd and it turns out to be wrong.

Chasing trends

This is arguably the strongest trading bias. Researchers on behavioural finance found that 39% of all new money committed to mutual funds went into the 10% of funds with the best performance the prior year. Although financial products often include the disclaimer that “past performance is not indicative of future results,” retail traders still believe they can predict the future by studying the past.

Humans have an extraordinary talent for detecting patterns and when they find them, they believe in their validity. When they find a pattern, they act on it but often that pattern is already priced in. Even if a pattern is found, the market is far more random than most traders care to admit. The University of California study found that investors who weighted their decisions on past performance were often the poorest performing when compared to others.

Overcoming Behavioural Finance tendencies

Behavioural biases are common obstacles to investment success. Even the most rational individuals are vulnerable to making poor investment decisions based on erroneous conclusions or emotional reactions to new information. Behavioural biases contribute to the often-documented tendency of investors to achieve inferior returns relative to market benchmarks. Investors who have a strategy for avoiding behavioural biases are more likely to earn investment success.

1. Focus on the process & set trading rules

There are two approaches to decision-making:

- Reflexive – going with your gut, which is effortless, automatic and, in fact, our default option.

- Reflective – logical and methodical, but requires effort to engage in actively

Relying on reflexive decision-making makes us more prone to deceptive biases and emotion and social influences. In addition to this, investors should set trading rules that never change. For example, if a stock trade loses 7% of its value, exit the position. Regard the rules as ‘unbreakable’ and don’t trade on emotion.

2. Manage emotions:

Studies show that investors feel greater pain from investment losses than satisfaction from investment gains. Emotions contributed to pain selling at several pivotal moments in 2016, notably in January in connection with concerns about China, as well as in the early hours following the Brexit vote in June and the election of President Donald Trump in November. Investors who calmly assessed the investment implications were more likely to benefit from the opportunities provided by each event.

3. Remember that what happened today will not necessarily happen tomorrow, or in the long term. And a little respect for the uncertainty of the market, and our own ability to correctly predict outcomes, helps.

4. Seek contrary opinions.

Investors are vulnerable to confirmation bias, as far too many investors seek validation from sources that support their investment thesis while avoiding opposing points of view. The best investors seek contrarian opinions, then evaluate the strengths of the competing arguments.

5. Be a “renter” not an “owner”. Investors often develop an unhealthy attachment to a stock. Sometimes the attachment is linked to a personal connection to the company; in other cases, investors fail to understand that a “great” company may not always be a “great” stock. Many successful investors think of their stocks as “rentals,” which creates the emotional distance necessary to remain objective about decisions whether to sell or keep existing holdings.

6. Don’t chase yesterday’s winners or trends, or blindly follow the market. “Performance chasing” is a common phenomenon, with money flowing into recent winners and away from recent losers. Investors mistakenly expect recent success to continue. However, performance often reverts to long-term averages, so chasing last year’s winners often leads to lagging performance and a vicious cycle of high turnover

7. Read and understand all available data regarding the fund you want to invest in, and especially look for information that is incongruent with your already conceived notions and beliefs. Look for dissenting voices, just to be on an even keel.

8. Thoroughly analyse funds before investing, regardless of their levels of success.

9. Have a detailed discussion with your financial advisor about market expectations, and what you can do in case of an economic slump.

The bottom line

You can’t avoid all behavioural bias but you can minimise the effect on your trading activities. Behavioural finance teaches us to invest by preparing, planning and by making sure we pre-commit.

“Investing success doesn’t correlate with IQ after you’re above a score of 25. Once you have ordinary intelligence, then what you need is the temperament to control urges that get others into trouble.”

-Warren Buffet